Our glorious Christmas and Easter hymns are too wonderful to sing just once a year! We should find great joy in celebrating these two events of redemptive history many times during the year. We have more hymns for those two seasons than could possibly all be sung during the short time they are observed on our calendars. Since the biblical events associated with Christmas and Easter are so very special, it’s not surprising to realize how many hymns have been written for those two events, some of which stretch back hundreds of years.

One of those whose origins go back a thousand years (!) is the Easter hymn, “Sing Choirs of New Jerusalem.” We sing a more recent 19th century translation of the Latin text that comes from Bishop Fulbert of Chartres. He was born in Italy about 960 and died in Chartres, France in 1028, having served as Bishop there from 1006 until his death. Having studied at Rheims, he was a pupil of Gerbert of Aurillac, who would later become Pope Sylvester II. Fulbert also taught and became head of the Cathedral school at Chartres. He lectured on many subjects, including medicine, and was able to attract many well-known scholars to the schools, thus making the Chartres institution one of the best schools of its time.

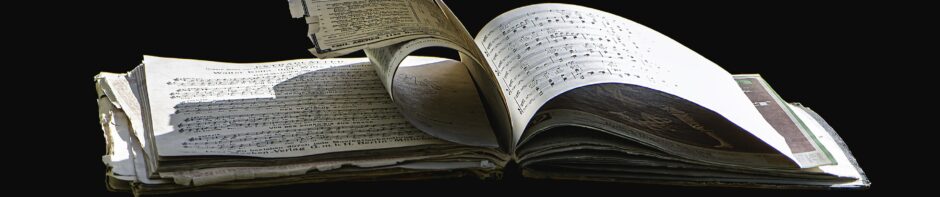

As Bishop, he entered into the political and theological controversies of his day. He was responsible for the advancement of the Nativity of the Virgin’s feast day on September 8 and for one of the many reconstructions of the Chartres Cathedral. Most of the available information about him is found in the letters he wrote from 1004 to 1028 to both secular and religious figures of the day. He left a substantial body of writings, including hymns, some of which were used in the British medieval “Sarum Breviary.” The original Latin text of this hymn began “Chorus novae Jerusalem,” and came to be used in British cathedrals and monasteries during the Easter season. It first appears in multiple 11th century manuscripts, and since Fulbert died in 1028, it must have become popular very rapidly.

The hymn as it appears today is a translation by Robert Campbell (1814-1868), originally in six stanzas. Numbers 3 and 5 of that original are generally omitted today. The modern text first appeared in Campbell’s “Hymns and Anthems for Use in the Holy Services of the Church within the United Diocese of St Andrews, Dunkeld, and Dunblane” (Edinburgh, 1850). The editors of “Hymns Ancient and Modern” altered Campbell’s text in various places, replaced the final stanza with a doxology, and added “Alleluia! Amen” to the hymn’s end. Other translations of the hymn by John Mason Neale, R. F. Littledale, R. S. Singleton and others were also in common use at the end of the 19th century.

Campbell was born at Trochmig, Ayrshire, in Scotland Dec. 19, 1814. While still a boy, he attended the University of Glasgow. Though showing from his earliest years a strong predilection for theological studies, he eventually settled on Scottish law as a profession. To this end he entered the Law classes of the University of Edinburgh, and in due course entered upon the duties of an advocate. Originally a Presbyterian, at an early age he joined the Episcopal Church of Scotland. He became a zealous and devoted churchman, directing his special attention to the education of the children of the poor.

His classical attainments were good, and his general reading extensive. In 1848 he began a series of translations of Latin hymns. In 1850, a selection of those, together with a few of his original hymns, and a limited number from other writers, was published in the 185o Edinburgh volume. This collection, known as the “St. Andrews Hymnal,”received the special sanction of Bishop Torry, and was used throughout the Diocese for some years. Two years after its publication, he joined the Roman Catholic Church. During the next sixteen years he devoted much time to the young and poor. He died at Edinburgh on December 29, 1868.

The first stanza begins with an invitation to sing. It refers to the “New Jerusalem” of Revelation 21:2 and uses “paschal victory” instead of the more frequent “paschal victim.” The second stanza describes Jesus as the Lion of Judah of the Old Testament and the fulfillment of the promise of Genesis 3:15, although the medieval text more probably had the idea of the Roman Catholic idea of the harrowing of hell in mind, an idea also present in stanza three. The fourth and fifth stanza incite the believer to worship the triumphant Christ. As already noted, the final stanza was added by the editors of “Hymns Ancient and Modern” and is a doxology, a common meter setting of the Gloria Patri.

The significance of the resurrection of Christ for our faith, destiny, race, and universe is so rich that a congregation needs many hymns to cover the topic satisfactorily. “Come, Ye Faithful, Raise the Strain” describes our deliverance from sin and sadness, as well as the exalted Christ’s bestowal of peace, the fruit of his redemptive work. “The Day of Resurrection” emphasizes the permanence of the resurrection and the importance of our seeing it aright. “Christ the Lord Is Risen Today” celebrates Christ’s defeat of death and our union with him in His resurrection. That has come to be the one hymn almost universally sung on Easter Sunday!

This hymn, “Sing, Choirs of New Jerusalem,” rounds out such a collection by celebrating not just the defeat of death but the destruction of the one who has the power of death, that is, the devil (stanza 2: Hebrews 2:14). By doing so in the language of the protoevangelium of Genesis 3:15, the poem interprets the resurrection according to the covenantal framework of the whole Bible: the Second Adam has triumphed over our first enemy, the penalty for sin has been paid, and all the conditions for life have been met (Romans 5:12-21). We have been made citizens of the new Jerusalem (stanza 1: Revelation 21–22).

Furthermore, Christ’s resurrection proclaims something … evidence that demands a verdict, as Josh McDowell put it … to every member of the human race past, present, and future: to the ungodly, doom (1 Peter 3:19), to believers, life (Romans 8:11), and to all for whom it is not yet too late, a call to repentance (Acts 2:24–38; 17:30–31). “Christ cries aloud through death’s domains / to wake th’imprisoned dead.” The consonant clusters of “Christ cries” connect this proclamation to the previous line’s crushing of the serpent’s head. (Note the symmetrical placement of the subsequent “d” sounds: as the consonants of the first accented syllable of line 2 return in the first two words of line 3, so the initial consonant of the “last” two words of line 3 returns in the “last” accented syllable of line 4.) Although the Latin poet had in mind the medieval idea of the harrowing of Hell (limbo), a doctrine not held by Protestants, the English translation expresses the thoroughly biblical idea of the proclamatory significance of the resurrection.

The first word of the hymn is an imperative to sing. Those doing the singing are “choirs” who employ their “sweetest notes.” Therefore, if any hymn warrants a quasi-choral style rather than the simple chordal texture developed over the centuries in Protestant churches for congregational singing, this is it. It is in an elaborate style, which in another hymn would distract congregants from the message. This actually strengthens the message here because the text itself directs our attention to the music. And, since poetry has said so much in so few words, music has room to contribute more than its usual share. British hymnologist J. R. Watson called the polyphony of LYNGHAM “astonishing (and invigorating),” yet most congregations, with a little practice, almost intuitively find their voices in it just fine.

The part writing is much easier than that in other insistently polyphonic tunes (compare with “Wonderful Grace of Jesus”). Occurring in the fourth line, the polyphony coincides with appropriate words in all stanzas. The “songs of holy joy” are plural. A cry “to wake the imprisoned dead” should astonish. “All saints in earth and heaven” bow. Finally, there’s nothing in corporate worship quite like contemplating, together with those whom one loves, a glory to be enjoyed “while endless ages run” and singing the line seven times (!), the tenors and basses four times, the sopranos and altos three times, in overlapping statements, especially on a Resurrection Sunday morning. There’s nothing like it in the world.

The hymn text is really quite unique. Generally, we expect a hymn to be addressed to the Lord. Often it’s addressed to fellow believers, or is calling on unbelievers to put their trust in Christ. Many are simply statements of truth proclaimed to all. But here, the audience is “choirs of new Jerusalem.” Are these other believers in our church fellowship of worshipping saints? Or is this addressed to those now in glory? Or both?

One of the marks of really good hymn text is that it is filled with clear quotations and/or allusions to scripture passages. That was wonderfully true of the hymns of Charles Wesley. It has been said that if all the Bibles in the world were lost, we could almost put it back together from lines from Wesley’s hymns! One of the best examples of that in his hymnody is with “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.” Look below at how many direct phrases have biblical connections.

Stanza 1

Sing, choirs of new Jerusalem, (Galatians 4:26-27)

your sweetest notes employ, (Psalm 81:2)

the paschal victory to hymn (2 Chronicles 30:21)

in songs of holy joy! (2 Samuel 6:5)

Stanza 2

For Judah’s Lion burst His chain (Revelation 5:5)

and crushed the serpent’s head. (Genesis 3:15)

Christ cries aloud through death’s domains (John 5:25)

to wake th’imprisoned dead. (Ephesians 2:15)

Stanza 3

Triumphant in His glory now, (Colossians 2:15)

to Him all pow’r is giv’n; (Matthew 28:18)

To Him in one communion bow, (John 5:23)

all saints in earth and heav’n. (1 Corinthians 1:2)

Stanza 4

All glory to the Father be,

all glory to the Son,

all glory to the Spirit be

while endless ages run. (Jude 24-25)

The tune LYNGHAM is a marvelous match for the triumphant nature of the text, and for the victorious nature of the event it celebrates. It’s opening line, in dotted rhythm, almost dances off the page! Its composer, Thomas Jarman (1776-1861) was born just days before Christmas in December, 1776 in Clipston, a small British village near the northern border of the County of Northampton. His father was not only a Baptist lay preacher, but also a tailor, and Thomas was brought up in the same trade, although his brother, John, followed his father’s calling to become a minister.

His natural taste for music, however, considerably interfered with his work, and he frequently struggled financially, from which only the extreme liberality of his publishers relieved him. One source said that his monetary problems led to his neglecting his work and soured his temperament. He was reportedly a man of fine, commanding presence, but self-willed, and endowed with a considerable gift of irony, as choirs frequently found.

He joined the choir of the Baptist chapel in his native village when quite a youth, and soon became the choirmaster there. He adopted music as a profession (with occasional returns to his old trade as a tailor), and was engaged as teacher of harmony and singing in many of the neighboring villages. He was a successful choir-trainer, spending several years at Leamington, and conducted concerts as well as services, for which he was constantly composing works. The village choir festival held under his direction at Naseby, in 1837, is said to have been the talk of the district for long after.

He spent some six or seven years at Leamington, during which time he enjoyed the friendship of C. Rider, a wealthy Methodist who did much good for the psalmody of Lancashire in his time. Jarman published an enormous quantity of music, including over six hundred hymn-tunes, besides anthems, services, and similar pieces. Amongst his many anthems written for special occasions there is one for the opening of the new Baptist chapel at Clipston. Another is a “Magnificat” for an Episcopal chapel at Leamington, where Thomas Jarman was called to assist the choir in their study and performance of psalmody. He lived to the age of eighty-five, dying in 1861, and was buried in the graveyard attached to the Baptist chapel at Clipston in Northampton.

Here is a link to the text and tune as played and sung on a Sunday morning.