When we come to the Lord’s Table, our pastors encourage us to give careful thought ahead of time about the seriousness and magnificence of all that is represented in this sacrament. Our colonial ancestors typically held a communion preparatory service before communion Sunday. It was a service devoted to a rehearsal of what Jesus accomplished by His atoning sacrifice and the need for self-examination to make sure those who approach the table do so with renewed repentance and faith, and a fresh commitment to obedience. At that preparatory service, it was customary to distribute pewter “tokens” to each adult. On communion Sunday, when the elements were served, often at tables set up in the church yard, one needed that token, like a ticket, in order to be allowed a seat at the table.

While we no longer see such valuable services and practices today, the need is still there to examine one’s self before partaking of the elements. This is evident in Paul’s instructions about the Lord’s Supper in 1 Corinthians 11:28-29. “Let a person examine himself, then, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment on himself.” This is why in Reformed churches there is the mandatory “fencing of the table,” when the pastor reminds attendees that the table is open to all, and only, who have repented of their sins and placed their trust in Christ, and whose profession of faith has been deemed credible by virtue of their being members in good standing of an evangelical church.

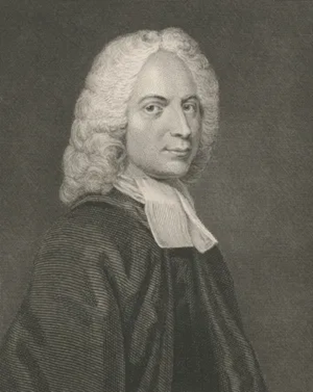

As part of the liturgy in coming to the Lord’s Table, it is typical in our churches to sing a hymn that prepares our hearts for this wonderful blessing of communion with the Lord, when our souls are nourished by feeding on Jesus’ body and blood by faith. Among the hymns that help us do that is Isaac Watts’ hymn, “How Sweet and Awesome Is the Place.” Written in 1707, its lyrics give eloquent expression to the attitudes and understanding that should dominate our thinking as we come to the Table. It is a much-appreciated and often-used hymn at communion services.

Isaac Watts (1674-1748), an English Nonconformist (Independent/Congregational) minister, known today as the “Father of English Hymnody,” was born in Southhampton, Hampshire, England. He is honored today as the father of English hymnody. The son of a Nonconformist, he studied at the Dissenting Academy at Stoke Newington, London, which he left in 1694. In 1696 he became tutor to the family of Sir John Hartopp of Stoke Newington (a center of religious dissent) and of Freeby, Leicestershire, and preached his first sermons in the family chapel at Freeby. He was appointed assistant to the minister of Mark Lane Independent Chapel, London in 1699 and in March 1702 became full pastor. He was apparently an especially inspiring preacher. Because of a breakdown in health (1712), he went to stay, intending a week’s visit, with Sir Thomas Abney in Hertfordshire, but he remained with the Abneys for the rest of his life.

Watts wrote educational books on geography, astronomy, grammar, and philosophy, which were widely used throughout the 18th century. He is now best known, however, for his hymns, having written about 650 of them. The famous hymns were written during Watts’s Mark Lane ministry. His first collection of hymns and sacred lyrics was “Horae Lyricae” (1706), quickly followed by “Hymns and Spiritual Songs” (1707), which included “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross,” “There Is a Land of Pure Delight,” and others that have become known throughout Protestant Christendom. The most famous of all his hymns, “Our God, Our Help in Ages Past” (from his paraphrase of Psalm 90), and “Jesus Shall Reign” (part of his version of Psalm 72), almost equally well known, were published in “The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament…” (1719). They are found in virtually every hymnal in print, and each of our modern hymnals will be found to contain man, many of his hymns. He also wrote religious songs especially for children; these were collected in “Divine Songs for the Use of Children” (1715).

The original text of this hymn penned by Watts began, “How Sweet and Awful is the Place.” When people use the word “awful” today, we mean that something is terrible, ugly, even repugnant. Of course, that is not at all what Watts meant. What he meant by that word in the early 18th century was that the place and event of corporate worship where we meet with the Lord is a place that is filled with awe, that attitude of deep reverence, recognizing that our God is present, as Psalm 29:2 and Psalm 96:8-9 say, in the beauty of His holiness. A better spelling to convey the meaning would be “awe-full,” as in “full of awe.” And so in most hymnals today, the text has been modernized to read, “How Sweet and Awesome Is the Place.” That still falls short of Watts’ intent, that this is a place that is filled with awe, since the Lord Himself is present.

There is a secondary theme in the text, and that is evident in that the hymn is sometimes included in the topical section of hymns regarding salvation, and specifically the doctrine of election. It could also, and perhaps more appropriately, be included in the section on effectual calling.

Stanza 1 speaks of the moments when believers gather for worship to celebrate the Lord’s Supper, most specifically. It is both sweet (pleasant and attractive, drawing us in a relaxed spirit) and awful (in some was terrifyingly fearful in reverence, causing us to pause and consider where we are, spiritually) in the very presence of God Himself. Watts spelled it out, that Christ is actually in our midst as we enter the doors of the sanctuary. Here we find Him to be administering not His anger, but His everlasting love, the most wonderful (“the choicest”) dimension of His character.

How sweet and awful is the place

with Christ within the doors,

while everlasting love displays

the choicest of her stores.

Stanza 2 describes how our hearts respond to this awful moment, with amazement that we who are so unworthy have been invited to this feast at the Lord’s Table. We are thankful, but we are also incredulous, asking Him directly, “Why was I a guest?” The fact that we would ask this is the thing that best demonstrates that we indeed are welcomed to come: that we realize that we don’t deserve this. We admire what we find here, and at the same stand stunned that we have actually been admitted as a guest.

While all our hearts and all our songs

join to admire the feast,

each of us cries, with thankful tongue,

“Lord, why was I a guest?”

Stanza 3 continues the question, “Why? Why me?” I would not have been able to hear His inviting voice unless He had enabled me to do so. Why did He? I was deaf to the invitation that came from His lips. Why did He give me hearing? The room where His presence is found is limited. Why did He grant me admission while there was still room? These questions become even more intense when I remember how many “thousands make a wretched choice.” And knowing that the one who is the bread of life offers Himself for spiritual food, why was I called out from among those others who “rather starve than come?”

“Why was I made to hear Thy voice,

and enter while there’s room,

when thousands make a wretched choice

and rather starve than come?”

Stanza 4 answers the question in part, not the “why” but the “what.” The only reason the Bible gives as to why any of us who have been invited to come have received that effectual call is nothing other than His sovereign love. It was “the same love that spread the feast that sweetly drew us in.” Here is why the hymn may be found in the hymnal section on effectual calling. Had He not called us, “we had still refused to taste, and perished in our sin.” Oh, how we need to remember that on those Sunday mornings when we receive the elements from the Lord’s Table!

‘Twas the same love that spread the feast

that sweetly drew us in;

else we had still refused to taste,

and perished in our sin.

Stanza 5 addresses the Lord in prayer, acknowledging that while we do not know why He has called us to Himself, pleading that He would “Pity the nations,” those multitudes that are still lost and hopeless in the darkness of sin, apart from His sovereign mercy. As we come to the Table, how appropriate that we would ask Him to “send Thy victorious Word abroad, and bring the strangers home.” Let the occasion of the celebration of the Lord’s Supper be a renewing of our prayer for the salvation of the nations, so that, as we sing in Psalm 67, “Let the peoples praise You, O God, let all the peoples praise You!”

Pity the nations, O our God,

constrain the earth to come;

send Thy victorious Word abroad,

and bring the strangers home.

Stanza 6 concludes our prayer in the same theme and sentiment, a hopeful longing for the day when we will “see Thy churches full, that all the chosen race may, with one voice and heart and soul, sing Thy redeeming grace.” We are assured that such a day will come, as Jesus promised in John 6:35-40 that all that the Father has given Him will come to Him, and that He will not lose one of them. And remember that He spoke this in the context of His offering Himself as the bread of life, the same context in which we sing this communion hymn.

We long to see Thy churches full,

that all the chosen race

may, with one voice and heart and soul,

sing Thy redeeming grace.

We sing it today to the tune ST. COLUMBA, an old Irish folk melody that perhaps has origins from several hundred years ago. The tune is best-known as the music for “The King of Love My Shepherd Is.” The tune’s first appearance in a hymnal, and apparently its first known appearance in print, was in the Irish 1864 “Church Hymnal,” where it was called a “Hymn of the Ancient Irish Church” and set to “Great Shepherd of thy people here [hear],” which is a common-meter text by John Newton. In this version, the melody is a relatively plain series of alternating whole and half notes. This musical arrangement was repeated in the 1874 edition of the hymnal, mildly revised, set to the same text by Newton, “Lord, of thy mercy hear our cry.” Here the tune was labeled ST. COLUMBA (named probably after the 6th century Irish missionary, Columba) while again being called a “Hymn of the Ancient Irish Church.” This version of the tune was repeated in the Appendix to the 1885 “Scottish Hymnal.”

Just a few years later, the tune appeared in “Ancient Music of Ireland from the Petrie Collection,” arranged for piano in 1877 by François Hoffman. The title is in reference to transcriptions of Irish folk tunes collected by George Petrie (1790–1866), president of the short-lived Society for the Preservation and Publication of the Melodies of Ireland (1851–1855). His manuscripts are now spread across three libraries in Ireland (National Library of Ireland, Trinity College Library, Irish Traditional Music Archive). The present location of the manuscript for this tune is unclear. In this published example, the tune was included in a section labeled “Specimens of the Ancient Church Music of Ireland,” and this melody was headed “Sung at the dedication of a church.” The first six bars were a bit more embellished than what had appeared in the Irish “Church Hymnal,” but the back half of the tune is the same.

A much larger, more comprehensive set of tunes from Petrie’s collection was edited by Charles Villiers Stanford and published as “The Complete Collection of Irish Music as Noted by George Petrie” (Parts I & II, 1902; Part III, 1905). This tune was included in Part II, No. 1043, labeled “Irish hymn sung on the dedication of a chapel—Co. of Londonderry.” In this instance, the repeated notes at the ends of the first and second half of the tune are not marked by ties, thus making it suitable for texts of 8.7.8.7, and here the triplet figure that we now find in the modern version in our hymnals was rendered in unequal rhythms.

At the time, Stanford was also serving on the committee for a new edition of “Hymns Ancient and Modern” (1904). In that collection, the tune appeared with “As now the sun’s declining rays,” a text by John Chandler, translated from a Latin text by Charles Coffin. This version of the tune is a strange cross between the Irish “Church Hymnal”rendition. The harmonization was left uncredited. Lastly, the pairing of ST. COLUMBA with “The King of Love My Shepherd Is” was made in the 1906 “The English Hymnal.” In the preface to that collection, the editors specifically lamented their inability to secure the rights to print “such beautiful tunes as Dykes’ ‘Dominus regit me’ or Stainer’s ‘In Memoriam.’” As a happy consequence, their choice of replacement has proven to be popular. On the page, the tune was credited as “Ancient Irish Hymn Melody (Original form),” and it is indeed very close to how it appeared in today’s hymnals including its format as a tune for 8.7.8.7. The harmonization was credited to Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924), one of the great names in Victorian British Anglican music, one of the founding members of the Royal College of Music. When this tune was included in “Songs of Praise” (1925), musical editor Ralph Vaughan Williams (one of Stanford’s students) changed the harmonization of the last chord of the first phrase, and this revised setting has been repeated in other collections.

In its present form, ST. COLUMBA has been called a gentle tune. It is set in 3:4 time, a rhythmic pattern that is usually joyful, and almost has the sweeping feel of a waltz. It is not difficult to learn or to sing, going up and down the scale. It has a comforting feel, fitting for a comforting text, a comforting prayer, thanking God for His great mercy to us.

Here is a link to the hymn from a recording from a Texas church.