Most hymnals today have a topical section called “morning” and also the next called “evening.” This includes hymns like “All Praise to Thee, My God, This Night,” “Abide with Me, Fast Falls the Eventide,” “Savior, Breathe an Evening Blessing,” “Now the Day Is Over,” “The Day Thou Gavest, Lord, Is Ended,” “Day is Dying in the West,” and “Softly Now the Light of Day.” These were familiar to those of us who grew up in a day when most evangelical churches had a worship service on Sunday evenings. This was usually a more informal service, sometimes called a “vesper service,” with more hymns being sung (often as people requested “favorites”), prayer requests fielded and offered, perhaps a testimony, and always Scripture and sermon.

How ironic that this section continues to be included in hymnals today, when it has become rare to find a church that still has a service on Sunday evening. For some, this loss is regarded as a sad sign of the times when “the Lord’s Day” has become merely “the Lord’s morning.” Historically, Sunday evening services were an emotional and psychological as well as spiritual joy for the covenant people of God, as the day began and ended in the Lord’s house. Some noted that it is significant that after the first and second Psalms (the first describing Jesus as that blessed man who sought the Lord whole-heartedly, and the second celebrating Jesus’ sovereign power over the rebellious kings of the earth as the begotten one anointed by the Father), the next two point to the beginning and ending of a day in worship. Psalm 3:5 reads, “I lay down and slept; I woke again, for the LORD sustained me,” a Psalm for the morning. And the next one is a Psalm for the evening, as we read in Psalm 4:8, “In peace I will both lie down and sleep; for You alone, O LORD, make me dwell in safety.”

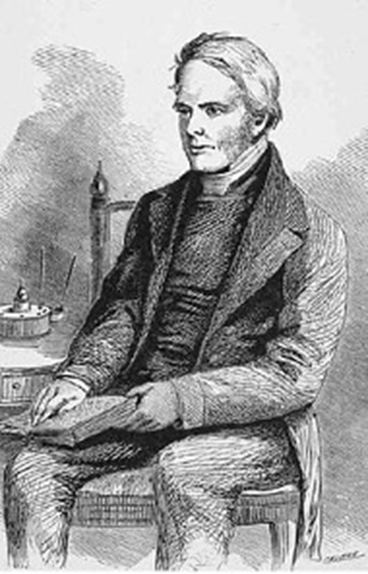

In the past, one of the best-known and often-sung evening hymns was “Sun of My Soul, Thou Savior Dear,” written in 1820 by John Keble (1792-1866), an English Anglican priest of extraordinary poetic giftedness. He became one of the leaders of the Oxford Movement (also known as the Tractarian Movement), inclining the Church of England to regain much of the liturgy and Latin hymnody of earlier days. Some of its proponents (though not Keble himself) joined the Roman Catholic Church. Keble College, Oxford, is named after him. Keble was born in Fairford, Gloucestershire, where his father, also named John Keble, was vicar of Coln St. Aldwyns. He and his brother Thomas were educated at home by their father until each went to Oxford.

In 1806, Keble won a scholarship to Corpus Christi College Oxford. He excelled in his studies and in 1810 achieved double first-class honors in both Latin and mathematics. In 1811, he won the university prizes for both the English and Latin essays and became a fellow of Oriel College. He was for some years a tutor and examiner at the University of Oxford.

While still at Oxford, he was ordained in 1816, becoming a curate to his father and then curate of St. Michael and St. Martin’s Church, Eastleach Martin, in Gloucestershire while still residing at Oxford. On the death of his mother in 1823, he left Oxford and returned to live with his father and two surviving sisters at Fairford. Between 1824 and 1835, he was three times offered a position and each time declined on the grounds that he ought not separate himself from his father and only surviving sister. In 1828, he was nominated as provost of Oriel College but not elected.

“Sun of My Soul, Thou Savior Dear” is taken from a fourteen stanza poem entitled “Evening,” dated November 25, 1820. It was included in what he had been writing, “The Christian Year,” a book of poems for the Sundays and feast days of the church year. It appeared in 1827 and was very effective in spreading Keble’s devotional and theological views. It was intended as an aid to meditation and devotion following the services of the Prayer Book. Though at first anonymous, its authorship soon became known, with Keble in 1831 appointed to the Chair of Poetry at Oxford, which he held until 1841. Victorian scholar Michael Wheeler calls “The Christian Year”simply “the most popular volume of verse in the nineteenth century.” Ninety-five editions of this devotional text were printed during Keble’s lifetime, and at the end of the year following his death, the number had arisen to a hundred-and-nine. By the time that the copyright expired in 1873, over 375,000 copies had been sold in Britain and 158 editions had been published. Despite its widespread appeal among the Victorian readers and the familiarity of certain well-known hymns, the popularity of Keble’s “The Christian Year” faded in the 20th century. As will be noted below, what we use as the hymn, “Sun of My Soul, Thou Savior Dear, was part of a lengthy poem in “The Christian Year,” with modern hymn text beginning with the third stanza of the original work.

In 1835, his father died, and Keble and his sister retired from Fairford to Coln. In the same year he married Charlotte Clarke. When the vicarage of Hursley in Hampshire vacant, it was offered to him, and he accepted. In 1836, he settled in that humble village, with a population of only 1500 people, and remained there for the rest of his life as a parish priest at All Saints’ Church. In all, he produced some 765 hymns. In 1857, he wrote one of his more important works, his treatise on “Eucharistical Adoration.” Keble died in Bournemouth on March 29, 1866 at the Hermitage Hotel, after visiting the area to try and recover from a long-term illness as he believed the sea air had therapeutic qualities. He is buried in All Saints’ churchyard, Hursley, which is the name given the tune most often used for the singing of his most famous composition.

In his country vicarage, he was not idle with his pen. In 1839 he published his “Metrical Version of the Psalms.” The year before, he began to edit, in conjunction with Drs. Pusey and Newman (of the Oxford Movement), the “Library of the Fathers.” In 1846 he published the “Lyra Innocentium” and in 1847 a volume of “Academical and Occasional Sermons.”His pen then seems to have rested for nearly ten years, when the agitation about the Divorce Bill called forth from him in 1851 an essay entitled, “An Argument for not proceeding immediately to repeal the Laws which treat the Nuptial Bond as Indissoluble.” In the popular sense of the word “hymn,” Keble can scarcely be called a hymnwriter at all. Very many of his verses have found their way into popular collections of hymns for public worship, but these are mostly centos, a patchwork of compositions from multiple places. Often they are violently detached from their context in a way which seriously damages their significance. Taking, however, the word “hymn” in the wider sense as a song of adoration to God, Keble stands in the very first rank of hymnwriters.

Keble has been described thus by one of his peers.

He was absolutely without ambition, with no care for the possession of power or influence, hating show and excitement, and distrustful of his own abilities…. Though shy and awkward with strangers, he was happy and at ease among his friends, and their love and sympathy drew out all his droll playfulness of wit and manner…. In personal appearance he was about middle height, with rather square and sloping shoulders, which made him look short until he pulled himself up, as he often did with ‘sprightly dignity.’ His head, says Mozley, ‘was one of the most beautifully formed heads in the world,’ the face rather plain-featured, with a large unshapely mouth, but the whole redeemed by a bright smile which played naturally over the lips; and under a broad and smooth forehead he had ‘clear, brilliant, penetrating eyes which lighted up quickly with merriment kindled into fire in a moment of indignation…. a quiet country clergyman, with a very moderate income, who sedulously avoided public distinctions, and held tenaciously to an unpopular School all his life.’

The hymn “Sun of My Soul, Thou Savior Dear” is often associated with Psalm 91:5 (“You will not fear the terror of the night”) or Psalm 139:11-12 (“If I say, ‘Surely the darkness shall cover me, and the light around me be night,’ even the darkness is not dark to You; the night is bright as the day, for darkness is as light with You”). The hymn pleads for the constant sense of Christ’s unwavering presence night and day in our lives. As such, it remains an excellent choice for an evening worship service on the Lord’s Day.

Stanza 1 asks the Lord to remain with us through each night. Keble drew his reference to Jesus as the Sun of righteousness from Malachi 4:2. Because He is God, it is not night when He is near because with Him the night shines as the day (Psalm 139:12). Therefore, we need never allow any earth-born cloud to arise and cause us to fear, since “the Lord is my light and my salvation” (Psalm 27:1).

Sun of my soul, Thou Savior dear, It is not night if Thou art near;

O may no earth-born cloud arise To hide Thee from Thy servant’s eyes!

Stanza 2 asks the Lord to be with us while we rest in sleep. God’s people have the promise that they can lie down in peace and sleep (Psalm 4:6-8). Even at night, our thoughts and meditations should be on the Lord and His word, as does “the blessed man” of Psalm 1:1-2. One such thought that will sustain us as we sleep is the hope of forever resting on our Savior’s breast, just as John, “the beloved apostle” did in this life (John 13:23).

When the soft dews of kindly sleep My wearied eyelids gently steep,

Be my last thought, how sweet to rest Forever on my Savior’s breast.

Stanza 3 asks the Lord to abide with us from morning until evening. We should want the Lord to abide with us day and night just as He did for a while with the disciples whom He met on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:29). Our attitude should be such that without Him we cannot live, because our desire should be to have Him living in us, as Paul described in Galatians 2:20. Also we should have the attitude that without Him we dare not die because our hope should be to depart and be with Him (Philippians 1:21-23).

Abide with me from morn till eve, For without Thee I cannot live;

Abide with me when night is nigh, For without Thee I dare not die.

Stanza 4 asks the Lord to watch over and help His wandering children. Sadly, it is all too possible for a child of God to wander back into sin (Galatians 6:1, James 5:19). The way in which one who has become a child of God does this is by spurning the voice of God which speaks through His word (Hebrews 3:12-13; 4:1-2). While we cannot expect God to save the unfaithful in their sins, we can hope that in some way the Lord might begin a work in seeking His erring children that will soften their hearts so that they will be more responsive, just as the shepherd goes out to find the lost sheep (Luke 15:1-7).

If some poor wandering child of Thine Has spurned today the voice divine,

Now, Lord, the gracious work begin; Let him no more lie down in sin.

Stanza 5 asks the Lord to bless especially those who suffer each night. God certainly does care for the sick and watches over them in their sufferings (James 5:13-16). It is God’s desire to enrich the poor, at least to provide for their needs as they put their trust in Him, seeking His kingdom and righteousness above all things (Matthew 6:33). Furthermore, as “the God of all comfort,” He is the source of all comfort to those who are mourning or in sorrow (2 Corinthians 1:3-4).

Watch by the sick; enrich the poor With blessing from Thy boundless store;

Be every mourner’s sleep tonight, Like infant’s slumbers, pure and light.

Stanza 6 asks the Lord to continue with us as we wake. When we arise each morning, we can look forward to the day in the presence of God (Psalm 139:17-18). Through the day we can, as “through the world our way we take,” look forward to the guidance of our God (Luke 1:77-79). And at all times, we can look forward to that day when we might ultimately awaken to Christ’s eternal salvation in heaven above (1 Peter 1:3-5).

Come near and bless when we wake, Ere through the world our way we take,

Till in the ocean of Thy love, We lose ourselves in heaven above.

The poem from which the stanzas of this hymn were taken begins,

’Tis gone, that bright and orbed blaze, Fast fading from our wistful gaze;

Yon mantling cloud has hid from sight The last faith pulse of quivering light.

It was intended more as a devotional poem than a hymn, but it has served very usefully through the years as an evening song. When night falls and I pillow my head in rest, I can still look up to the Lord as the light of my life for all my needs because He is the “Sun of My Soul.” Oh, that we might find the myriad blessings of a Lords’s Day evening service return to common practice, and with it, the singing of hymns like this one.

The tune HURSLEY is based on the old Latin hymn “Te Deum.” It first appeared as an anonymous melody in the “Katholisches Gesangbuch” of Vienna around 1774 in the form “Grosser Gott” for the German versification of the “Te Deum.” It is viewed as an early French Huguenot tune by an anonymous composer. That older form is often used with another hymn, “Holy God, We Praise Thy Name.” The present long-meter form is usually attributed to an otherwise unknown musician named Peter or Paul Ritter (1760-1846). It is dated 1892. This tune was the personal choice of Keble and his wife as a suitable melody for “Sun of My Soul” and first appeared with this text in the 1855 “Metrical Psalter” of W. J. Irons and Henry Lahee. The modern harmonization was made in 1861 by English church musician William Henry Monk (1823-1889).

Here is a link to the singing of the hymn.