The doctrine of election is one of the most wonderful, foundational, and widespread teachings in all of the Bible. There are several words commonly found throughout the scriptures which express the concept. When translated into English, these include not only elect/election, but also predestined/predestination, foreordained/foreordination, called, and chosen. A quick search in any concordance will show numerous passages where these terms are found in God’s Word. Even the word grace, when understood properly, points to this truth. That is reflected in the way we often speak not merely of grace, but more particularly of sovereign grace.

Even when any of these words are absent, the twin central truths of human depravity and divine sovereignty in salvation permeate all portions of the Word of God. Because we are dead in our sins and enslaved to our old nature (as Paul taught in the opening verses of Ephesians 1), our only hope is that God would change our unwilling and undeserving hearts to enable and motivate us to reach out to Him. We need to be born again, as Jesus told Nicodemus in John 3. But as human beings cannot cause themselves to be born physically, neither could any of us cause ourselves to be born again spiritually. We read in 1 Peter 1:3, “according to His great mercy, He has caused us to be born again.”

These doctrines of sovereign grace have been embraced by the greatest theologians throughout the history of the church. These teachings are not the perspective of some recent fringe group in Christendom. No, they have been taught joyfully and without apology by such respected and trustworthy theologians in past ages as Augustine, Luther, Calvin, Knox, Edwards, Spurgeon, Ryle, and in seminaries like Princeton, Reformed, Westminster, Knox, Greenville, and Covenant. In more recent years we find these doctrines of grace in the teachings of Pink, Boice, Packer, Kennedy, Sproul, Piper, and Mohler. In fact, the doctrine is present in every one of the major confessions and creeds of the Reformation era: the Lutheran Augsburg Confession, the Heidelberg Catechism, the Westminster Standards, and the London Baptist Confession.

These doctrines should be a source of immense happiness for believers. Our only hope of salvation is found in the hope that we find by understanding that there was nothing we did to initiate or deserve or achieve the status of being a redeemed, adopted child of God. It was only because of His great love for us that we have been brought into the kingdom of God. We embrace this biblical doctrine with great joy. How sad then that it is so hard to find it represented in the vast majority of hymnals used today in the west. One of the few hymns that enables us to sing these truths with such joy is the hymn “Tis Not That I Did Choose Thee,” written in 1836 by Josiah Condor (1789-1855).

Josiah Condor, the fourth son of Thomas Condor, was born in Falcon Street, Aldersgate, London. His grandfather, Dr. John Condor, was a noted Dissenter clergyman. His father, Thomas, was also a strong Nonconformist and so Josiah grew up in this environment. At five years of age, smallpox blinded him in his right eye. Fearing the possible loss of his other eye, he was sent to Hackney for electrical treatment. His physician became his teacher, and carried him through the fundamentals of French, Latin and other studies. At the age of fifteen, he became assistant to his father in a metropolitan book store. Here he had opportunity to further cultivate his mind by judicious reading; and his occupation with books improved his taste for literature. He became a prominent London Congregationalist, an abolitionist, and took an active part in seeking to repeal British anti-Jewish laws. Subsequent to 1824, he composed a series of descriptive works, called the “Modern Traveller,” which appeared in thirty volumes.

In 1810 we find him in co-operation with Ann and Jane Taylor and Eliza Thomas (who later became his wife) and some others in publishing a book called “The Associate Minstrels.” It secured a second edition in 1812. He also edited a newspaper called the “Patriot” but was never out of financial problems, even though he persevered, encouraged by his Lord. He once had a fall from his horse, which laid him aside in much pain and suffering. But at that time he could write, “Fix my heart on things above; make me happy in Thy love.” It is not known how Condor was brought to Christ, but there is definite evidence of his confidence in the sovereign grace of God in the hymns that he wrote.

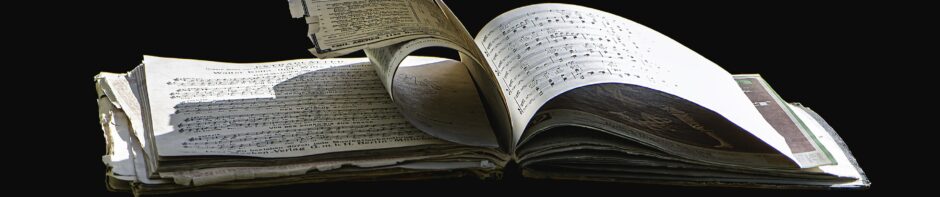

As a hymn writer Condor ranks with some of the best of the first half of the 19th century. His finest hymns are marked by much elevation of thought expressed in language combining both force and beauty. They generally excel in unity, and in some the gradual unfolding of the leading idea is masterfully presented. The outcome of a deeply spiritual mind, they deal chiefly with the enduring elements of religion. They vary in meter, in style and in treatment, saving them from the monotonous mannerism which mars the work of many hymn writers of his time. In the year 1837 he published “The Congregational Hymn Booke, a Supplement to Watts.”It contained sixty-two compositions of his own, with four composed by his wife. So popular did it become, that during the first seven years of its publication ninety thousand copies were sold – an immense circulation forthose days. The popularity of Condor’s hymns was substantial until the early 20th century, after which they were seldom found in hymnals. In 1917, more of them were in common use in Great Britain and America than those of any other writer of the Congregational body, except for those of Isaac Watts and Philip Doddridge.

The hymn called “Hearer of Prayer,” is reported to have been written under the following circumstances. “While riding, Mr. Conder fell from his horse and was compelled to take to his bed in a trying season. He was not only suffering from pain, but feared becoming a permanent cripple. His affairs, too, were in a condition that required his utmost activity. This confinement summoned all his fortitude, and led him to constant supplication. It was thus he wrote the following lines in which the bravehearted preacher is seen at his best—bold, earnest, importunate.”

O Thou God who hearest prayer

Every hour and everywhere,

For His sake, whose blood I plead,

Hear me in my hour of need:

Only hide not now Thy face,

God of all-sufficient grace!

Leave me not, my Strength, my Trust;

Oh, remember I am dust;

Leave me not again to stray;

Leave me not the tempter’s prey;

Fix my heart on things above;

Make me happy in Thy love.

Condor embraced the Calvinistic theology of Congregationalists of his day, a conviction that is sadly lacking in most of that branch of Christendom today, as well as in much of shallow sentimental evangelical theology (or lack of theology!). Subsequent to 1824, he composed a series of descriptive works, called the “Modern Traveller,” which appeared in thirty volumes). The Bible clearly teaches that we are sinners (Isaiah 64:6; Romans 3:23). Therefore we are unable to “choose” Jesus. Instead, Jesus has chosen us! Jesus said in John 15:6, “You did not choose Me, but I chose you”. There is nothing new about this. In Deuteronomy 7:7-9, Moses told the Israelites “the Lord your God has chosen you.” Moses went on to make it clear that the choosing had nothing to do with how special the people were, but everything about God being faithful to his own promise. This thought comes through very strongly in verses one and two of Condor’s hymn. Some hymnals have included a third stanza, which is basically a doxology.

The lyrics clearly present the classic understanding of the doctrine of sovereign election. How wonderful to sing it with the evangelical warmth with which Condor has expressed it.

Stanza 1 focuses on my own fallen, enslaved nature that would never have sought Christ. An honest examination of the stubbornness and coldness of the remnants of sin that remains in my heart even after regeneration reveals how impossible it would have been in my former state to have ever wanted or been willing to surrender my heart to God. As Condor correctly wrote, “this heart would still refuse Thee, hadst Thou not chosen me.” This is why the doctrine of sovereign grace is so wonderful to us. It reminds us that we would still be in our sin if God had not ordained us “of old,” before the foundation of the earth (Ephesians 1:5). The doctrine of divine election is our only, and our all-sufficient hope. His grace has not only cleansed me, it has re-oriented my entire life “that I should live to Thee.”

‘Tis not that I did choose Thee,

For, Lord, that could not be;

This heart would still refuse Thee,

Hadst Thou not chosen me.

Thou from the sin that stained me

Hast cleansed and set me free;

Of old Thou hast ordained me,

That I should live to Thee.

Stanza 2 focuses on God’s mighty grace that took the initiative to come to me and change me. Condor calls it “sovereign mercy,” and it is exactly that. It required a mighty work to change my nature, and only God has that kind of might. He effectually (effectively) called me “and taught my op’ning mind.” He has taught me things about myself and about Himself that I could never have discovered on my own, and never would have believed, unless He had performed that powerful regenerating work in my heart. I would have been in love with the world, “enthralled” by its lusts and pleasure, “blind” to the glories of true religion revealed in God’s Word and made attractive to my renewed mind. The final phrase comes right from 1 John 4:10. “In this is love, not that we have loved God but that He loved us

‘Twas sovereign mercy called me

And taught my op’ning mind;

The world had else enthralled me,

To heav’nly glories blind.

My heart owns none before Thee,

For Thy rich grace I thirst;

This knowing, if I love Thee,

Thou must have loved me first.

The tune SAVOY CHAPEL is only one of several possibilities that have been chosen for this 7.6.7.6.D meter. It was written in 1887 by John Baptiste Calkin (1827-1905). Born in London, he was reared in a musical atmosphere. Studying music under his father, and with three brothers, he became a composer, organist, and music teacher. At the age of 19, he was appointed organist, precentor, and choirmaster at St. Columbia’s College, Dublin, Ireland from 1846-1853. From 1853 to 1863 he was organist and choirmaster at Woburn Chapel, London. From 1863 to 1868, he was organist of Camden Road Chapel. From 1870 to 1884 he was organist at St. Thomas Church, Camden Town. In 1883 he became professor at Guildhall School of Music and concentrated on teaching and composing. He was also a professor of music and on the council of Trinity College, London, and a member of the Philharmonic Society (1862). In 1893 he was made a fellow of the College of Organists. He and his wife, Victoire, had four sons, each of whom followed a musical career. He wrote much music for organ and scored string arrangements, sonatas, dues, etc. He died at Hornsey Rise Gardens.

Here is a link to the hymn from the Trinity Hymnal.