In a worship service, we are coming into the presence of God. As we learn from Psalm 139: 9-10 (“if I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there Your right hand shall lead me and Your right hand shall hold me”) and from Matthew 18:20 (“wherever two or three are gathered in My name, behold, I am there in the midst of them”), He is us with always, and we are never apart from Him, especially when we come into His house to worship Him. And it’s what He promised in the Great Commission in Matthew 28:20 (“And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age”).

But there is something unique about the corporate gathering of God’s people on the Lord’s Day. He delights to come and meet with us to receive our adoration and hear our prayers. The realization that we will be in the presence of the King of the universe should make a powerful impact on us, causing us to think twice before we arrive, so that our hearts are prepared to meet with Him. In addition, it should cause us to be richly energized and filled with a special excitement as the service begins.

We typically call the initial prayer an invocation, calling upon the Lord to come and meet with us to bless us with His presence through His Word, as it is read and preached to us and as we pray and sing it to Him. But in a sense, He is already there when we arrive. It’s not so much that we are invoking His presence, because He is already present, having called us and then waiting for us to come at His invitation. In our invocation, what we are more accurately doing is asking Him to energize our hearts and minds so that we can more fully and consciously enter into His presence.

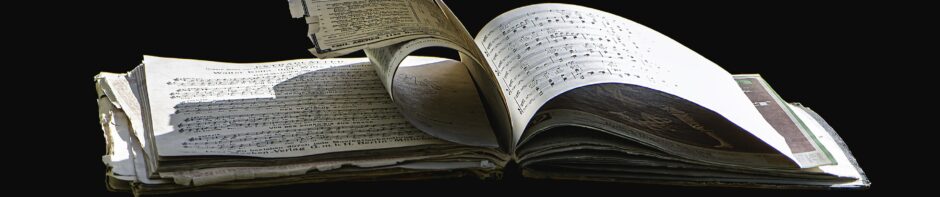

Our hymnals have a section about entering into worship, sometimes with the heading “the opening of worship.” Here we will find hymns like “Brethren, We Have Met to Worship,” “Jesus, Where’er Your People Meet,” “Father, Again in Jesus’ Name We Meet,” “God Himself Is with Us,” and “Lord Jesus Christ, Be Present Now.” To these we must add the 18th century hymn “Open Now Thy Gates of Beauty,” written in 1732 by Lutheran pastor Benjamin Schmolck (1672-1737).

He was born at Brauchitschdorf on December 21, 1672, the son of a Lutheran pastor. He entered the Gymnasium at Lauban in 1688, and spent five years there. After his return home he preached for his father a sermon which so struck the patron of the church that he made Benjamin an allowance for three years to enable him to study theology. He matriculated at Michaelmas in 1693, at the University of Leipzig, where he came under the influence of J. Olearius and J. B. Carpzov. Throughout his life he retained the character of their teaching: a warm and living practical Christianity, but Churchly in tone and not excessively Pietistic.

In the autumn of 1697, after completing his studies at Leipzig During his last year in Leipzig he supported himself mainly by the proceeds of occasional poems written for wealthy citizens, for which he was also crowned as a poet. In the autumn of 1697 he completed his studies, and in the summer of that year he returned to Brauchitzchdorf to help his father. In 1701 he was ordained as his assistant.

On February 12, 1702 he married Anna Rosina, daughter of Christoph Rehwald, a merchant in Lauban, and in the end of the same year was appointed deacon of the Friedenskirche at Schweidnitz in Silesia. As the result of the Counter-Reformation in Silesia, the churches in the principality of Schweidnitz had been taken from the Lutherans, and for the whole district the Peace of Westphalia (1648) allowed only one church (and that only of timber and clay, without tower or bells), which the Lutherans had to build at Schweidnitz, outside the walls of the town. The three clergy attached to this church had to minister to a population scattered over some thirty-six villages, and were moreover hampered by many restrictions, such being unable to bring communion to a sick person without a permit from the local Roman Catholic priest. Here Schmolck remained till the close of his life, becoming in 1708 archdiaconus, in 1712 senior pastor, and in 1714 pastor primarius and inspector.

Probably as the result of his exhausting labors he was paralyzed by a stroke on Laetare (Mid-Lent) Sunday, 1730, which for a time laid him aside altogether, and after which he never recovered the use of his right hand. For five more years he was still able to officiate, preaching for the last time on a Fastday in 1735. But two more paralyzing strokes followed. Then he was diagnosed with a cataract. He found relief for a time by a successful operation, but it returned again incurably. For the last months of his life he was confined to bed, until release from his infirmities came. He died on the anniversary of his wedding, on February 12, 1737.

Schmolck was well known in his own district as a popular and useful preacher, a diligent pastor, and a man of wonderful tact and discretion. It was however his devotional books, and the original hymns they contained that brought him into wider popularity, and carried his name and fame all over Germany. There have been long lists of his works and of the various editions through which they passed. It is rather difficult to trace the hymns, as they were copied from one book of his into another. He was the most popular hymnwriter of his time, and was hailed as the “Silesian Rist,” as the “second Gerhardt.” It is true that he did not possess the soaring genius of Gerhardt. Nor had he even Gerhardt’s concise, simple style, but instead was fond of high-sounding expressions, of plays upon words, of far-fetched but often recurring contrasts, and in general of straining after effect, especially in the pieces written in his later years. It has been written that he wrote a great deal too much, and in later works without proper attention to concentration or to proportion.

Besides Cantatas, occasional pieces for weddings, funerals, etc., he is the author of some 900 hymns. These were written for all sorts of occasions, and range over the whole field of church, family, and individual life. Naturally they are not all of equal and lasting value. A deep and genuine personal religion, and a fervent love to the Savior, inspire his best hymns. They are not simply thought out but felt. They come from the heart and carry to the heart. The best of them are also written in a clear, flowing, forcible, natural, popular style, and abound in moralistic sayings, easy to be remembered. Of these, many are more suited for family use than for public worship. Nevertheless, they very soon came into extensive use, not only in Silesia, but all over Germany.

As with so many of the great German hymns (generally referred to as chorales), our English translation comes to us from Catherine Winkworth (1827-1878), who produced this one in 1863. Born on the edge of the city of London, she was the daughter of a silk merchant. His business took the family to Manchester during the time of the Industrial Revolution.

She spent a year in Germany in Dresden, during which her interest in German hymnody developed. She published a collection of her translations of a number German hymns in 1854, with another collection following in 1858. During 1863, she published “The Chorale Book for England,” with “Christian Singers of Germany” coming off the press in 1869. According to “The Harvard University Hymn Book,” Winkworth “did more than any other single individual to make the rich heritage of German hymnody available to the English-speaking world.”

She was also deeply involved in promoting women’s education as the secretary of the Clifton Association for Higher Education for women, and a supporter of the Clifton High School for Girls, where a school house is named after her, and a member of the Cheltenham Ladies’ College. She was likewise governor of the Red Maids’ School in the city of Bristol. She died suddenly of heart disease near Geneva on July 1, 1878 and was buried in Upper Savoy. A monument to her memory was erected in Bristol Cathedral.

In stanza 1 the lyrics begin with a call to the gates of Zion, to the church invisible, to open and welcome the worshippers who have approached through Christ. In the succeeding stanzas, the words are appropriately addressed to the God whom we meet there. Our souls are filled with joyful anticipation of the privilege that will be ours when our Savior, “who answers prayer,” answers our prayer that He come and bring us to Himself. How blessed indeed “is this place, filled with solace, light, and grace!”

Open now thy gates of beauty,

Zion, let me enter there,

where my soul in joyful duty

waits for Him who answers prayer.

Oh, how blessed is this place,

filled with solace, light, and grace!

In stanza 2 we call on the Lord Himself, conscious of the fact that we are welcomed into His presence in the throne room of the entire universe. There is a double request here: that as we come before Him that He would also come unto us. And then we identify the reason for our coming: that as we find Him, we would adore Him, the only one worthy of our total adoration. And then the stanza ends with a sweetly personal request, that since to be in His presence here and now is to find this to be “a heaven on earth.” And so we ask that He would enter into our hearts, making that the temple where He will display His grace and glory!

Lord, my God, I come before Thee,

come Thou also unto me;

where we find Thee and adore Thee,

there a heav’n on earth must be.

To my heart, O enter Thou,

let it be Thy temple now!

In stanza 3 we describe further what our intent is in coming into the beauty of His presence, and that is to chant (or sing) His praise. What a great analogy Schmolck has offered here, that bringing our hearts into His presence is like having Him sow a seed inside our soul, that once planted will grow to produce a luxuriant harvest of “precious sheaves,” meaning sheaves of praise. And so we expect that our worship would prove to be “fruitful unto life in me.”

Here Thy praise is gladly chanted,

here Thy seed is duly sown;

let my soul, where it is planted,

bring forth precious sheaves alone,

so that all I hear may be

fruitful unto life in me.

In stanza 4 we look past the moments of our worship service, asking that the Lord would use this special time to advance our spiritual growth, making our faith “increase and quicken.” And we confess before Him that in our weakness, we need His strength to maintain that “gift divine” of spiritual life in our hearts, lest we succumb to the many temptations we face. They key to finding that strength from Him will be found in His written Word, as we know from Psalm 119:11, “Thy Word have I hidden in my heart that I might not sin against Thee.” Schmolck adds another image, that of His Word serving like a star to guide us “though life,” which reminds us of the star in the east that guided the Magi to Mary and Joseph and Jesus.

Thou my faith increase and quicken,

let me keep Thy gift divine,

howsoe’er temptations thicken;

may Thy Word still o’er me shine

as my guiding star through life,

as my comfort in my strife.

In stanza 5 we conclude with a prayer that God would speak to us in our time of worship. Of course, we do not expect that to be in physically audible tones or by special revelation, but rather through His Word as it is preached and prayed and sung and confessed. Here the request is not so much about the way He would do so as it is with our readiness to respond, as we become aware of what He is saying to us through his Word. We promise that we will listen with a genuine desire that His will might be done. The reference to His feeding His people certainly points us to Jesus as the bread of life, and to His Word as the nourishment and guidance and strengthening of our souls. When that is true, then it is indeed in the midst of worship that “the fountain flows” and that we find “balm for all our woes.”

Speak, O God, and I will hear Thee,

let Thy will be done indeed;

may I undisturbed draw near Thee

while Thou dost Thy people feed.

Here of life the fountain flows,

here is balm for all our woes.

The tune NEANDER comes from Joachim Neander (1650-1680). He was born at Bremen as the eldest child of the marriage of Johann Joachim Neander and Catharina Knipping, which took place on September 18, 1649. His father was then master of the Third Form in the Paedagogium at Bremen. The family name was originally Neumann (Newman) or Niemann, but the grandfather of the poet had assumed the Greek form of the name, i.e. Neander. After passing through the Paedagogium he entered himself as a student at the Gymnasium Illustre (Academic Gymnasium) of Bremen in October of 1666. German student life in the 17th century was anything but refined, and Neander seems to have been as riotous and as fond of questionable pleasures as most of his fellows.

In July of 1670, Theodore Under-Eyck came to Bremen as pastor of St. Martin’s Church, with the reputation of a Pietist and holder of conventicles, private gatherings for spiritual encouragement. Not long after Neander, with two like-minded comrades, went to service there one Sunday, in order to criticize and find it a matter for amusement. But the earnest words of Under-Eyck touched his heart; and this, with his subsequent conversations with Under-Eyck, proved the turning-point of his spiritual life.

In the spring of 1671 he became tutor to five young men, mostly, if not all, sons of wealthy merchants at Frankfurt-am-Main, and accompanied them to the University of Heidelberg, where they seem to have remained till the autumn of 1673, and where Neander learned to know and love the beauties of Nature. The winter of 1673-74 he spent at Frankfurt with the friends of his pupils, and here he became acquainted with Pietist leaders Philip Spener and Johann Jakob Schütz. In the spring of 1674 he was appointed Rector of the Latin school at Düsseldorf.

Finally, in 1679, he was invited to Bremen as unordained assistant to Under-Eyck at St. Martin’s Church, and began his duties about the middle of July. The post was not inviting, and was regarded merely as a stepping stone to further advancement, the remuneration being a free house and 40 thalers a year. The Sunday duty involved a service with sermon at the extraordinary hour of 5 a.m. Had he lived, Under-Eyck would doubtless have done his best to get him appointed to St. Stephen’s Church, the pastorate of which became vacant in September, 1680. But meantime Neander himself fell into physical decline, and died at Bremen on May 31st, 1680.

Neander was the first important hymn-writer of the German Reformed Church since the times of Blaurer and Zwick. His hymns appear to have been written mostly at Düsseldorf, after his lips had been sealed to any but official work. The true history of his unfortunate conflict has now been established from the original documents, and may be summarized thus.

The school at Düsseldorf was entirely under the control of the minister and elders of the Reformed Church there. The minister from about July, 1673, to about May, 1677 was Sylvester Lürsen (a native of Bremen, and only a few years older than Neander), a man of ability and earnestness, but jealous, and, in later times at least, quarrelsome. With him Neander at first worked harmoniously, frequently preaching in the church, assisting in the visitation of the sick, etc. But he soon introduced practices which inevitably brought on a conflict. He began to hold prayer meetings of his own, without informing or consulting minister or elders; he began to absent himself from Holy Communion, on the ground that he could not conscientiously communicate along with the unconverted, and also persuaded others to follow this example; and became less regular in his attendance at the ordinary services of the Church. Besides these causes of offence he drew out a new timetable for the school, made alterations on the school buildings, held examinations and appointed holidays without consulting anyone.

The result of all this was a Visitation of the school on November 29, 1676, which resulted then in his suspension from school and pulpit on February 3, 1677. On Feb. 17 he signed a full and definite declaration by which “without mental reservations” he bound himself not to repeat any of the acts complained of; and thereupon was permitted to resume his duties as rector but not as assistant minister. The suspension thus lasted only 14 days, and his salary was never actually stopped. The rumored statements that he was banished from Düsseldorf, and that he lived for months in a cave in the Neanderthal near Mettmann are therefore without foundation. Still his having had to sign such a document was a humiliation which he must have felt keenly, and when, after Lürsen’s departure, the second master of the Latin school was appointed permanent assistant pastor, this feeling would be renewed.

Neander thus thrown back on himself, found consolation in communion with God and Nature, and in the composition of his hymns. Many were without doubt inspired by the scenery of the Neanderthal (a lovely valley with high rocky sides, between which flows the little river Düssel). A number were circulated among his friends at Düsseldorf in MS., but they were first collected and published after his relocation to Bremen. In this way, especially in the district near Düsseldorf and on the Ruhr, Neander’s name was honored and beloved long after it had passed out of memory at Bremen.

Many of Neander’s hymns were quickly received into the Lutheran hymnbooks, and many remain in use. The finest are the jubilant hymns of Praise and Thanksgiving, such as his lyrics translated as “Prase to the Lord, the Almighty,” and sung to the tune LOBE DEN HERREN. He has also been recognized for those setting forth the Majesty of God in His works of beauty and wonder in Nature. As was typical of the Pietists and of German Reformed Covenant Theology, they are of a decidedly subjective cast, but for this the circumstances of their origin, and the fact that the author did not expect them to be used in public worship, will sufficiently account. But the glow and sweetness of his better hymns, their firm faith, originality, Scriptural character, variety and mastery of rhythmical forms, and genuine lyric character fully entitled them to the high place they hold.

Here is a link to a portion of the text, sung on a Sunday morning at New York’s Riverside Church.