Why do you come to corporate worship on the Lord’s Day morning? Many legitimate reasons could be offered, and we should be conscious of many of them as helpful, legitimate motivations that bring us together in the Lord’s House. But among them must surely be the expectation and the desire that Jesus Himself would call us to Himself, would meet with us, would teach us from His Word and would make that Word effective in causing us to grow to maturity as sons and daughters of God.

Having ascended bodily into heaven, we do not expect the Lord to be physically present with us until He returns at the end of the age. But He does meet with us spiritually through His Word. When it is read and preached, we hear Him speaking to us. The Apostle Paul wrote in 1 Thessalonians 2:13, “And we also thank God constantly for this, that when you received the word of God, which you heard from us, you accepted it not as the word of men but as what it really is, the word of God, which is at work in you believers.”

In many places in Scripture He has promised to do just that. Psalm 122 expresses the joy that we should feel as we respond to His call: “I was glad when they said unto me, ‘Let us go to the house of the Lord.’” Isaiah 55:10-11 assures us that God’s word will not return without accomplishing what He has sent it to do. And Jesus promised believers that wherever two or three meet in His name, He will be there in their midst (Matthew 18:20).

We typically begin a worship service with a prayer called an “invocation.” In that prayer, combined with a Scripture invitation, we are calling on God to meet with us. And we are bold to do so because His Word tell us that He delights to meet with His people, and that He does so through his Word. But a better concept, and a more emotionally uplifting perspective, is that, by His Word the Lord Jesus is the one calling us to come.

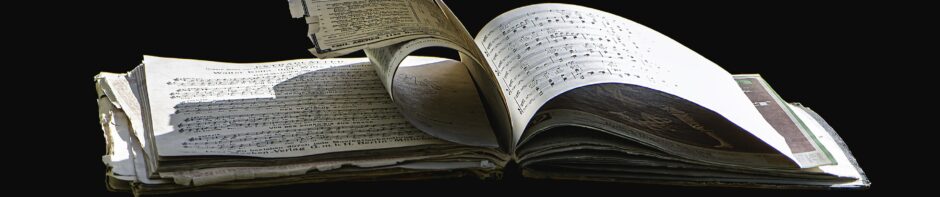

This is the message of one of the classic hymns in the church’s repertoire, “Blessed Jesus, at Thy Word,” written by German chaplain Tobias Clausnitzer (1619-1684). Numerous arrangements of this text with its most familiar tune, LIEBSTER HERR JESU, abound in organ and choral literature of many centuries. Like many of the most wonderful hymns of the post-Reformation period, it comes following after the terrible ravages of the Thirty Years’ War of 1618-1648, when untold millions died in Germany. The combined toll from battlefield conflict, starvation from the destruction of food stores, and the rampant diseases spread from corpses in the field contributed to unimaginable suffering from common folk throughout the country as warring armies moved back and forth, leaving devastation in their wake.

The Lutheran chorales of the 16th century were very focused on the essentials of justification: salvation by faith in Jesus alone. In contrast, many of the chorales of the 17th century became more personal, dealing with the concept of sanctification and trusting the Lord through such difficult times. Among them, of course, was Martin Rinkart’s composition, “Now Thank We All Our God,” written when he was called on to conduct multiple funerals in a single day, including that of his own wife. And these were also the years of Germany’s greatest hymn writer Paul Gerhardt (1607-1676), whose texts we sing in “O Sacred Head Now Wounded” and “Awake, My Heart with Gladness.”

Tobias Clausnitzer was born at Thum, near Annaberg, in Saxony, probably on February 5th, 1619. After studying at various Universities, and finally at Leipzig (where he graduated M.A. in 1643), in 1644 he was appointed chaplain to a Swedish regiment. In that capacity he preached the thanksgiving sermon in St. Thomas Church, Leipzig, on “Reminiscere” Sunday, 1645 (the second Sunday in Lent) on the accession of Christina as Queen of Sweden. He also preached the thanksgiving sermon at the field service held by command of General Carl GutavWrangel at Weiden, in the Upper Palatine, on January 1, 1649, after the conclusion of the Peace of Westphalia that brought the Thirty Years War to an end. In 1649 he was appointed first pastor at Weiden, and remained there (being also appointed later a member of the Consistory, and inspector of the district,) until his death, on May 7, 1684.

Clausnitzer’s hymn “Blessed Jesus, at Thy Word” appears for the first time in 1663, accompanied by a subtitle “Vor der Predig,” or “before the sermon,” possibly a recommendation coming from the writer himself. Later, in the “Evangelisches Gesangbuch,” it appears under “Eingang und Ausgang,” suggesting its use at the beginning or ending of the service. The hymn may also be used “as a prayer for illumination, or at the opening of worship.” All of these possibilities fit the text, with the last perhaps being the most appropriate, even as the opening hymn in the service.

The thematic material of “Blessed Jesus, at Thy Word” alludes to many New Testament references. The initial image is drawn from Cornelius’ statement to Peter that his household has assembled in order to hear what God has given Peter to say to them (Acts 10:33). The second stanza adapts the imagery of the creation account in Genesis 1:1-3 as a description of the congregation awaiting enlightenment through Jesus’ word. The third stanza relies on Jesus’ own self-description as the Light of the World (John 8:12; 9:5) as well as the epithet “Light from Light” in the Nicene Creed. Line 3 may be an allusion to Romans 8:26: “the Spirit helps us in our weakness. For we do not know what to pray for as we ought, but the Spirit Himself intercedes for us with groanings too deep for words.”

As with so many of the German chorales, in this hymn we use the English translation by Catherine Winkworth (1827-1878). Her translations were polished and yet remained close to the original. Educated initially by her mother, she lived with relatives in Dresden, Germany, in 1845, where she acquired her knowledge of German and interest in German hymnody. After residing near Manchester until 1862, she moved to Clifton, near Bristol. A pioneer in promoting women’s rights, Winkworth put much of her energy into the encouragement of higher education for women. She translated a large number of German hymn texts from hymnals owned by a friend, Baron Bunsen. Though often altered, these translations continue to be used in many modern hymnals.

She was said to have been a person of remarkable intellectual and social gifts, and very unusual attainments. Hymnologist John Julian, in his 1907 “Dictionary of Hymnology” wrote that “what specially distinguished her was her combination of rare ability and great knowledge with a certain tender and sympathetic refinement which constitutes the special charm of the true womanly character.” Another wrote that her religious life afforded “a happy example of the piety which the Church of England discipline may implant…..The fast hold she retained of her discipleship of Christ was no example of ‘feminine simplicity,’ carrying on the childish mind into maturer years, but the clear allegiance of a firm mind, familiar with the pretensions of non-Christian schools, well able to test them, and undiverted by them from her first love.”

Stanza 1 sings that it is God’s Word (perhaps both written in Scripture as well as Jesus Himself, the incarnate Word of John 1) that draws us to Himself. In Winkworth’s translation, the words of the hymn come across with a sweet intimacy. And so if our attitude is right, our hearts and souls will be stirred up and burn with us when we hear the scriptures, just as did with the two disciples on the road to Emmaus when they heard Jesus open the scriptures to them (Luke 24:32). Through these teachings, as we are taught, hear, and learn from the Father, God draws us to Christ (John 6:44-45).

Blessed Jesus, at Thy word

we are gathered all to hear Thee;

let our hearts and souls be stirred

now to seek and love and fear Thee,

by Thy teachings sweet and holy,

drawn from earth to love Thee solely.

Stanza 2 sings that God’s Word gives us knowledge. Not only that, God has provided all things that pertain to life and godliness through the knowledge of Him who called us by glory and virtue (2 Peter 1:3). This knowledge is provided by the Holy Spirit, who breaks our night with the beams of truth revealed in that which He guided the inspired apostles and prophets to write (Ephesians 3:3-5). Thus, through His work in revealing the scriptures, the Spirit wins us and works all good within us because He is the one who convicts the world of sin, righteousness, and judgment (John 16:7-13).

All our knowledge, sense, and sight

lie in deepest darkness shrouded,

’til Thy Spirit breaks our night

with the beams of truth unclouded.

Thou alone to God can win us;

Thou must work all good within us.

Stanza 3 sings further that God’s Word imparts light, something we need even after our regeneration, since so much of the old nature remains. God Himself is light (1 John 1:5), and He opens our ears and hearts by the word which reveals unto us the Spirit’s pleading and thus brings “light to our feet and a lamp to our path” (Psalm 119:18, 105). In return, we should bless Him with prayers and praises (Revelation 4:9-11).

Glorious Lord, Thyself impart,

Light of light, from God proceeding;

open now our ears and heart,

help us by Thy Spirit’s pleading;

hear the cry Thy people raises,

hear and bless our prayers and praises.

Stanza 4, written by an unknown author, dates to around 1707. In this English translation by Catherine Winkworth, she included it. It first appeared in her “Lyra Germanica” of 1858. It was probably intended to be used with Christian Gellert’s 1757 hymn, “Jesus Lives, and So Shall I.” It is a typical Gloria Patri text so often found as a final stanza to a hymn or a Psalm in Anglican worship. Whenever we praise God, we are praising Father, Son, and Holy Ghost (Matthew 28:18-19). It is only as we trust their revealed word that we can obtain true consolation (2 Corinthians 1:3-5). This consolation will guide us while we here below must “wander” until that time comes when we sing God’s praises “yonder” (Revelation 15:1-4).

Father, Son, and Holy Ghost,

praise to Thee and adoration!

Grant that we Thy Word may trust

and obtain true consolation,

while we here below must wander,

’til we sing Thy praises yonder.

The tune almost exclusively associated with this hymn, known as LIEBSTER JESU (named after the first two words in German), was composed by Johann Rudolph Ahle (1625-1673). Ahle’s tune was first published in “Neue geistliche auf die Sonntage” (1664) as the setting for an advent hymn by pastor Franz Joachim Burmeister’s (1633-1672) “Ja, er ist’s, das Heil der Welt.” It first appeared associated with this hymn in 1687, after having been altered from the original.

Ahle was Cantor (song leader) of St. Andreas’ Church and director of the Erfurt music school (1646-1654) where he had studied theology. Later, he also became organist at St. Blasius’ Church in Mühlhausen (1654), beginning to compose organ music there, and subsequently served as town councilor (1655) and mayor (1661) of the same city. He died there in 1673. Ahle was an active music educator and tune writer that published treatises on singing and helped develop a new style of church music influenced by Italian opera. He, along with others working around the same time, called his church tunes “sacred arias.” He wrote more than 400 florid, ornamented sacred arias intended for soloists, chorus, or solo singers and instruments, and not originally intended for congregational use.

The musical developments with which Ahle was involved were also closely connected to the political strife related to the Thirty Years War that these composers and writers lived through; a period in which, according to British hymnologist Eric Routley (speaking specifically of Ahle’s work) wrote, “all this new energy is put through a narrower channel, the intensity increases, and we get such masterpieces as the two tunes of Ahle, LIEBSTER JESU and ES IST GENUG.… Taken very slowly as a solo, LIEBSTER JESU makes a profound impact.”

LIEBSTER JESU was one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s (1685-1750) favorite chorale melodies, appearing in six different settings in his works. The version we encounter in hymnals today is not the florid one originally crafted by Ahle and set by Bach, which was in a dotted and flourished rhythm, but an altered version with straight quarter notes. This has been true of most of the German chorales, even of “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.” While Ahle’s first version is more soloistic, it had shifted to a more congregational version associated with Clausnitzer’s text by 1687.

Here is a link to the singing of the four stanzas.