The September 10, 2025 assassination of Charlie Kirk, founder and leader of “Turning Point USA,” has deeply shaken this country in a way unmatched by very many other events, coming just one day before the 24th anniversary of the 9/11 attack by Islamic terrorists. At the young age of 31, Kirk had, for the last decade, had an enormous influence, especially on young adults – and particularly young men – as a promoter of conservative values. Speaking on college and university campuses across the US, Kirk’s announced theme was “Prove Me Wrong!” He invited any who wanted to do so to come to the microphone and challenge him. He was able to powerfully, and usually persuasively, counter their liberal views on a variety of topics, and to do so with impressive knowledge and respect and affection for these students.

What many, especially of an older generation, had not realized until after an assassin’s bullet took his life, was that he spoke with impressive eloquence and deep conviction, not just of his conservative political views (as a close ally of President Donald Trump – indeed the one primarily responsible for generating such great support for Trump among young adults in the 2024 election), but also of his gospel knowledge and personal faith in the Lord Jesus as his Savior. His dominant themes included faith, family, and country, all related to a central theme of freedom (the word he wore on his shirt!). He urged these students to stand up for traditional values on their liberal campuses, to get married and have children, and to get connected to a Bible-believing church.

Those themes were not only prominent in his speeches, they were prominent in his life. And they may well become even more prominent after his death, based on initial reactions of many who have been emboldened to “stand up for Jesus.” His widow, Erika, delivered an amazing heart-felt tribute and challenge on national television just days after his assassination, speaking eloquently of her confidence in the goodness of God and her trust in Jesus in this dark time. And within ten days, the Turning Point offices had been flooded with 62,000 requests for new campus chapters!

And so when that bullet ended his life, it may well have sparked a real “turning point” for the nation. It is not without merit to see this assassination as part of a spiritual battle. Satan hates the truth, especially the truth of the gospel, and has used even physical violence to block efforts to make that gospel known. Jesus warned that we should expect to see that there would be those who think that by attacking faithful followers of Jesus, they are doing something good (“They will put you out of the synagogues. Indeed, the hour is coming when whoever kills you will think he is offering service to God,” John 16:2).

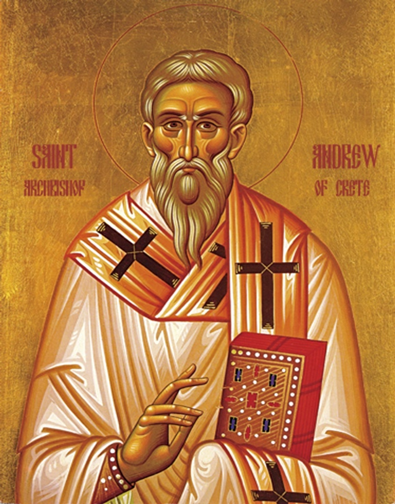

One of the oldest hymns in our hymnals speaks dramatically of this contrast between good and evil. “Christian, Dost Thou See Them” was written by Saint Andrew of Jerusalem (660-732), Archbishop of Crete. He was born to Christian parents in Damascus, but embraced the monastic life at Jerusalem, whence his name. Andrew was mute until the age of seven. According to historians, he was miraculously cured after receiving Holy Communion. He began his ecclesiastical career at fourteen in the Lavra of Saint Sabbas the Sanctified, near Jerusalem, where he quickly gained the notice of his superiors. Theodore, the “locum tenens” of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem (745-770) made him his Archdeacon, and sent him to the imperial capital of Constantinople as his official representative at the Sixth Ecumenical Council (680-681), which had been called by Emperor Constantine IV to counter the heresy of Monothelitism (the idea that though Jesus had two natures – human and divine – he had only one will).

Shortly after the Council, he was summoned back to Constantinople from Jerusalem and appointed Archdeacon at the “Great Church of Hagia Sophia,” where the amazing multi-domed building still stands. Eventually, Andrew was appointed to the metropolitan see of Gortyna, in Crete. Although he had been an opponent of Monothelitism, he nevertheless attended the Conciliabulum of 712, in which the decrees of the Ecumenical Council were abolished. In the following year, he repented of having embraced Monotheletism and returned to orthodoxy. Thereafter he occupied himself with preaching, composing hymns, and other literary ministries. As a preacher, his discourses are known for their dignified and harmonious phraseology, for which he is considered to be one of the foremost ecclesiastical orators of the Byzantine Era.

Church historians have no consensus as to the exact date of his death. What is known is that he died on in the island of Hierissus, near Mitylene, about 732, while returning to Crete from Constantinople, where he had been on church business. His relics were later moved to Constantinople. In 1349, a Russian pilgrim, Stephen of Novgorod, saw his relics at the Monastery of Saint Andrew of Crete in Constantinople. Seventeen of his homilies are extant, the best, not unnaturally, being on Titus the bishop of Crete. He is the author of several Canons, “Triodia,” and “Idiomela,” the most celebrated being “The Great Canon.” At modern Skala Eresou on Lesbo (ancient Eresos) is a large, early Christian basilical church in honor of Saint Andrew.

Today, Saint Andrew is remembered primarily as a hymnographer. He is credited with the invention (or at least the introduction) of the canon, a new form of hymnody, into the liturgy. Previously, the portion of the Matins service which is now the canon was composed of chanting the nine biblical canticles, with short refrains inserted between scriptural verses. Saint Andrew expanded these refrains into fully developed poetic Odes, each of which begins with the theme of the scriptural canticle, but then goes on to expound the theme of the feast being celebrated that day, whether the Lord, the Theotokos, a saint, or the departed.

His masterpiece, the “Great Canon” (also known as the “Canon of Repentance”), is the longest canon ever composed with 250 strophes (similar to what we would today call a stanza). It is written primarily in the first person, and goes chronologically through the entire Old and New Testaments, drawing examples, both negative and positive, which it correlates to the need of the sinful soul for repentance and a humble return to God. It is divided into four parts (called “methymony”) which are chanted at “Great Compline” on the first four nights of “Great Lent” (one part per night). Later, it is chanted in its entirety at Matins on Thursday of the fifth week of Great Lent.

The hymn is especially relevant at this point in our national history, as Americans are witnessing an incredibly evil and mean-spirited response to the Kirk assassination from people who demonstrate an almost irrational hatred for him and all dimensions of his message, both political and religious. These responses include absolute lies about what he said at his rallies and in his interviews, accusing him of being a man filled with hatred toward those with whom he disagreed. This is despite the voluminous record of his actual words, tone of voice, and actions, which belie all those falsehoods. These responses even go so far as to ignore and mock the enormous grief felt by Kirk’s widow with their two very young children.

And so we sing a hymn which acknowledges that such evil really does exist in the world around us. “Christian, dost thou see them on the holy ground, how the powers of darkness rage they steps around?” And we must response, “Yes, we do see them; and it tempts us to give in to fear!” Each stanza begins with that kind of sentiment in the first part. But then the hymn goes on in the second half of each stanza to challenge us to be bold in the face of that evil, standing firm in our confidence that the Lord has promised to be with us and to guide the future to a glorious end.

The English translation of the ancient text most often found today in hymnals is that written in 1862 by John Mason Neale (1818-1866). He was an English Anglican priest, scholar, and hymnwriter, who was associated with the Anglo-Catholic movement of the 19th century. He worked on and wrote a wide range of holy Christian texts, including obscure medieval hymns, both Western and Eastern. Among his most famous hymns is the 1853 “Good King Wenceslaus,” set on St. Stephen’s Day in the liturgical calendar, known as Boxing Day in the United Kingdom.

Neale was born in London, and educated at Sherborne School, Dorset and Trinity College, Cambridge. At the age of 22, Neale was the chaplain of Downing College, Cambridge, where he was affected by the Oxford Movement and became interested in church architecture. He helped to found the Cambridge Camden Society (afterwards known as the Ecclesiological Society). The society advocated for more ritual and religious decoration in churches, and was closely associated with the Gothic Revival. Neale’ s first published address was made to the society on November 22, 1841. He was ordained as a priest in 1842. He was briefly incumbent of Crawley in Sussex but was forced to resign due to a chronic lung disease. The following winter he lived in the Madeira Islands, where he was able to do research for his “History of the Eastern Church.” In 1846 he became warden of Sackville College, an almshouse at East Grinstead, an appointment which he held until his death.

In 1854 Neale co-founded the Society of Saint Margaret, an order of women in the Church of England dedicated to nursing the sick. Many Protestants of the time were suspicious of the restoration of Anglican religious orders. In 1857, Neale was attacked and mauled at a funeral of one of the Sisters. Crowds threatened to stone him or to burn his house. He received no honor or preferment in England, and his doctorate was bestowed by Trinity College in Connecticut. He was also the principal founder of the “Anglican and Eastern Churches Association.” A result of this organization was the “Hymns of the Eastern Church,” edited by John Mason Neale and published in 1865.

Neale was strongly high church in his sympathies, and had to endure a good deal of opposition, including a fourteen years’ suspension by his bishop. Neale translated the Eastern liturgies into English, and wrote a mystical and devotional commentary on the Psalms. However, he is best known as a hymnwriter and especially translator, having enriched English hymnody with many ancient and medieval hymns translated from Latin and Greek. For example, the melody of “Good King Wenceslaus” originates from a medieval Latin springtime poem, “Tempus adest floridum.” More than anyone else, he made English-speaking congregations aware of the centuries-old tradition of Latin, Greek, Russian, and Syrian hymns.

The 1875 edition of “Hymns Ancient and Modern” contains 58 of his translated hymns; the 2906 “English Hymnal” contains 63 of his translated hymns and six original hymns by Neale. His translations include “All Glory, Laud, and Honor,” “O Come, O Come, Emmanuel,” “Of the Father’s Love Begotten,” “Good Christian Men, Rejoice,” “Come, Ye Faithful, Raise the Strain,” “O Sons and Daughters, Let Us Sing,” “Christ Is Made the Sure Foundation” and “Jerusalem the Golden.”

The words to “Christian, Dost Thou See Them” are addressed as if spoken from one believer to another, perhaps like a preacher calling on his congregation to be alert to the evil around them, but at the same time to be assured that the Lord will strengthen us in our resistance, and carry us safely to our heavenly goal. The musical setting from John B. Dykes very helpfully sets the first two lines of each stanza in the key of B-flat minor, and then moves instantly to the key of B-flat major. This accentuates the dark mood of the first half, before changing to the bright mood of the second half of each stanza.

Stanza 1 contrasts the ominous sight of the powers of darkness that we see threatening us … with the challenge to rise up in the strength of the cross to smite them, “counting gain but loss.”

Christian, dost thou see them on the holy ground,

How the pow’rs of darkness rage thy steps around?

Christian, up and smite them, counting gain but loss,

In the strength that cometh by the holy cross.

Stanza 2 contrasts the emotional feel of these powers that tempt us to respond in sinful ways … with the challenge to not give in with trembling but instead of being downcast, engage in the battle.

Christian, dost thou feel them, how they work within,

Striving, tempting, luring, goading into sin?

Christian, never tremble, never be downcast;

Gird thee for the battle, watch and pray and fast.

Stanza 3 contrasts what we hear as evil forces mock us with our spiritual responses … with the bold profession that we will not give up on praying, but will continue until the peace comes.

Christian, dost thou hear them, how they speak thee fair?

“Always fast and vigil? Always watch and prayer?

Christian, answer boldly, “While O breathe I pray!”

Peace shall follow battle, night shall end in day.

Stanza 4 contrasts Jesus’ words of empathy from His own weariness … with His words of assurance that our efforts will bring us to the end of sorrow when we are gathered near His throne.

Hear the words of Jesus: “O My servant true:

Thou art very weary, I was weary too.

But that toil shall make thee someday all Mine own,

And the end of sorrow shall be near My throne.”

The music commonly used today for the hymn was written in 1868 by John Bacchus Dykes (1823-1876), and English clergyman and hymnwriter. He was born in Hull, England, the fifth son of a ship builder. By the age of 10, Dykes played the organ at St. John’s Church in Myton, Hull, where his paternal grandfather (who had built the church) was vicar and his uncle (also Thomas) was organist. He was taught by the Hull organist George Skelton. He also played the violin and the piano. He studied first at Kingston College, Hull.

Dykes matriculated in 1843 (with the surname Dikes) at Katharine Hall, Cambridge. There he was the second Dykes Scholar: the second beneficiary after his elder brother, Thomas, of an endowment established in 1840 in honor of his grandfather. As an extra-curricular subject, he studied music under Thomas Attwood Walmisley, whose madrigal society he joined. He also joined the Peterhouse Musical Society (later renamed the Cambridge University Musical Society), becoming its fourth President. He graduated B.A. in 1847 as Dykes, and M.A. in 1851. Dykes was appointed to the curacy of Malton, North Yorkshire, in 1847. He was ordained deacon at York Minster in January 1848. He was awarded the Mus. Doc. degree by Cambridge in 1849.

In 1849 Dykes was appointed a minor canon of Durham Cathedral (an appointment which he held until his death), and shortly thereafter to the office of precentor. Between 1850 and 1852 he lived at Hollingside House, which later became the official residence of the Vice Chancellor of the University of Durham. In 1862 he relinquished the precentorship on his appointment to the living of St Oswald’s, Durham, situated almost in the shadow of the Cathedral, where he remained until his death in 1876.

Dykes was from an evangelical family background. He moved to an Anglo-Catholic in the Church of England during his Cambridge years, and ultimately became a “ritualist.” He was in sympathy with the high church Oxford Movement. At this period, antagonism between the evangelical and Anglo-Catholic wings of the Church of England was sharp. A test case concerned the Brighton-based Rev. John Purchas (1823–72) who, as a consequence of a Privy Council judgment which bore his name, was compelled to desist from such practices as facing east during the celebration of Holy Communion, using wafer bread, and wearing vestments other than cassock and surplice. One London critic saw his worship style characterized by Lord Shaftesbury as “in outward form and ritual…the worship of Jupiter or Juno.” He was pursued through the courts, until he resigned his living in 1882.

Dykes treatment at the hands of the evangelical party, which included Bishop Charles Baring, was largely played out locally. Archdeacon Edward Prest held strongly to anti-ritualist views. The situation in County Durham in 1851 was that Wesleyan Methodist congregations outnumbered the Anglicans. Something on which Baring and Dykes agreed was that the strength of nonconformity reflected on failures of the Church of England. The Dean of Durham, from 1869 William Charles Lake, was on the other hand a high churchman, and not an opponent of ritualism, who put his views on the issue on record in a letter to “The Times” in 1880. He took on Baring over restoration of the cathedral, and succeeded shortly after Dykes had died.

Baring campaigned against ritualistic practices, insisting on that from those he was expected to license. In 1874 Dykes published an open letter, criticizing Baring’s position.Dykes’ failure to change Baring’s stance was followed by a gradual deterioration in his physical and mental health. It necessitated absence (which was to prove permanent) from St. Oswald’s from March, 1875. Rest and the bracing Swiss air proving unsuccessful in improving his condition, Dykes went to recover on the south coast of England.

Dykes was admitted to a “lunatic asylum,” Ticehurst House, in East Sussex, and died on January 22, 1876, aged 52. Some have viewed that Dykes’s ill-health was a consequence of overwork, exacerbated by his clash with Bishop Baring. He was buried in the “overflow” churchyard of St. Oswald’s, a piece of land for whose acquisition and consecration he had been responsible a few years earlier. He shares a grave with his youngest daughter, Mabel, who died, aged 10, of scarlet fever in 1870. Dykes’ grave is now the only marked grave in what, in later years, was transformed into a children’s playground.

Dykes has been called “perhaps the most significant High Church composer in the Victorian Church of England.” This standing was despite his main efforts having been as a parish priest in the Tractarian tradition, rather than as a musician. He is best known for over 300 hymn tunes that he composed. Most significant was his speculative submission in 1860 of tunes to the music editor William Henry Monk for what became very influential, “Hymns Ancient and Modern.”

Here is a link to the four stanzas as sung in worship (with a slightly altered text).